I’m going to present a (pretty limited) analysis of the gun control debate assuming the truth of two apparently robust social scientific findings:

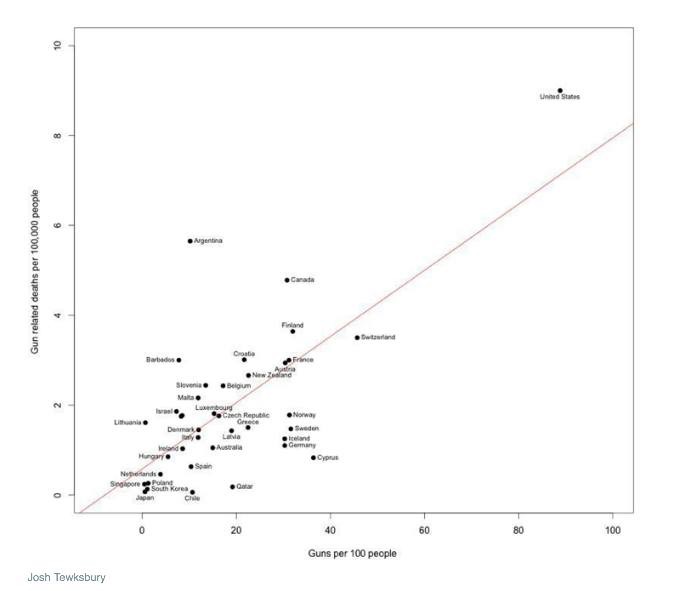

1. Cross-country analyses show a strong correlation between gun violence and gun availability.

2. Bans and prohibitions are particularly bad ways of dealing with problems or harms stemming from the availability of some object, substance or service.

I’m not at all equipped to evaluate 1 at any particular depth, but I’ve heard it reported and repeated by policy wonks and politicians on both sides of the political aisle. And, here’s a useful graph:

I know a little more about 2. It turns out that if you want to curb the bad social consequences associated with the use of some object, substance or service, other forms of regulation are typically better than prohibitions or bans at securing the policy goals and in ways that are less harmful and wasteful. Prohibitions and bans tend to raise prices in ways that redirect, rather than eliminate, production processes, supply chains, marketing techniques and consumer use. The ways bans do this are predictable and tend to make things worse.

So, for example, with the prohibition of drugs, we get organized criminal organizations that compete, usually violently, to monopolize markets and trade routes. This is bad. We also get drugs more concentrated and potent (like designer, synthetic or home concoctions) that are both easier to transport (smuggle) and more dangerous to consume. This is also bad.

Again, these bad social consequences associated with the war on drugs were eminently predictable as a straightforward playing out of the generalization in 2. If not, then it would mean that without a drug war, or without one as vigorously prosecuted, the social consequences of drug use would have been worse, other things being equal. This is implausible given the empirical evidence.

Say we ban assault rifles. 2 predicts that this will grow the illicit demand market and the comparable incentive for illicit suppliers and supply. The effects would be similar to those in the case of illicit drugs in the sense that the ban would redirect, rather than eliminate, the market. This is not a good way to deal with gun violence if 1 is right and the most significant factor is gun availability. If we assume that gun markets exhibit the same basic features of other markets, most of the explanation for how easy it is to access guns are things like existing supply and price levels, which are marginally impacted by various regulatory costs, like waiting periods and licensing and reporting requirements.

But 1 and 2 suggest that we should be asking things like “what would work best to affect these costs and margins in socially desirable ways?” There’s a clear and consistent convergence on the futility of bans and prohibitions. I understand that it isn’t very intuitive that availability is a (or, the most) significant factor but prohibition doesn’t work. But, first, consider the case of drugs again. It’s likely that the use of highly addictive and dangerous opioids is higher where there’s a higher availability of drugs, yet it’s still the case that drug prohibition is an utter social disaster. Second, regardless of whether you find it intuitive, this is simply what the best social science tells us about the effects of bans and prohibitions. In short, you’d find yourself in a very dubious epistemic position to deny it -- roughly the same position as you would be in if you rejected any other view that reflects a substantial scientific consensus.

To be clear: the argument here isn’t that prohibition wouldn’t affect the availability of guns; rather, it’s that prohibition wouldn’t affect their availability in socially desirable ways.

So what would work better than bans to reshape the market in guns to produce better social consequences? Yikes, I don’t know. I’m just a philosopher. But it would be surprising, I think, if the largest influence on the gun market, and so the largest influence on the mass production and relative availability of guns and the types of guns available, didn’t have something to do with the biggest spender on them. Compared to US federal and state government contracts, the private citizen market for weaponry amounts effectively to, if you’ll permit me to use a technical term, diddly squat. Imposing a ban on private ownership and exchange wouldn’t affect the supply side of the equation at all, and 1 suggests that’s what we should be concerned about.

The level of production and availability of weaponry in the US is driven by massive military, federal agency and state government spending. The impact of this spending on availability isn’t just that government surplus units can find their way into private hands. I’m sure that happens, but much more significant is the way government contracting magnitudes drive economies of scale for production, signal expansion in the industry, and incentivize both new firms and more and more units. Assault rifles are designed and produced with military and quasi-military applications in mind. This is the biggest market. The private consumer market is just spillover for producers. Second amendment enthusiasts and private protection stalwarts aren’t shaping supply. And waiting periods, registration and licensing requirements, magazine restrictions and excise taxes have little effect. Ditto buy-back programs or mandatory liability insurance. None of these measures are likely to make a significant difference on supply in the US when military spending is as high as it is.

Government expenditure on weaponry functions as a subsidy for guns. Subsidize something only if you want to get more of it. I recommend not doing this anymore (or drastically reducing this expenditure). Prohibition just makes things worse. Piecemeal regulations avoid the most significant problems associated with prohibition, but I doubt that any regulatory scheme would have an effect on reshaping the market in ways that would have a significant impact on weapons production (or tragic shootings) as long as total spending remains so high.

1. Cross-country analyses show a strong correlation between gun violence and gun availability.

2. Bans and prohibitions are particularly bad ways of dealing with problems or harms stemming from the availability of some object, substance or service.

I’m not at all equipped to evaluate 1 at any particular depth, but I’ve heard it reported and repeated by policy wonks and politicians on both sides of the political aisle. And, here’s a useful graph:

I know a little more about 2. It turns out that if you want to curb the bad social consequences associated with the use of some object, substance or service, other forms of regulation are typically better than prohibitions or bans at securing the policy goals and in ways that are less harmful and wasteful. Prohibitions and bans tend to raise prices in ways that redirect, rather than eliminate, production processes, supply chains, marketing techniques and consumer use. The ways bans do this are predictable and tend to make things worse.

So, for example, with the prohibition of drugs, we get organized criminal organizations that compete, usually violently, to monopolize markets and trade routes. This is bad. We also get drugs more concentrated and potent (like designer, synthetic or home concoctions) that are both easier to transport (smuggle) and more dangerous to consume. This is also bad.

Again, these bad social consequences associated with the war on drugs were eminently predictable as a straightforward playing out of the generalization in 2. If not, then it would mean that without a drug war, or without one as vigorously prosecuted, the social consequences of drug use would have been worse, other things being equal. This is implausible given the empirical evidence.

Say we ban assault rifles. 2 predicts that this will grow the illicit demand market and the comparable incentive for illicit suppliers and supply. The effects would be similar to those in the case of illicit drugs in the sense that the ban would redirect, rather than eliminate, the market. This is not a good way to deal with gun violence if 1 is right and the most significant factor is gun availability. If we assume that gun markets exhibit the same basic features of other markets, most of the explanation for how easy it is to access guns are things like existing supply and price levels, which are marginally impacted by various regulatory costs, like waiting periods and licensing and reporting requirements.

But 1 and 2 suggest that we should be asking things like “what would work best to affect these costs and margins in socially desirable ways?” There’s a clear and consistent convergence on the futility of bans and prohibitions. I understand that it isn’t very intuitive that availability is a (or, the most) significant factor but prohibition doesn’t work. But, first, consider the case of drugs again. It’s likely that the use of highly addictive and dangerous opioids is higher where there’s a higher availability of drugs, yet it’s still the case that drug prohibition is an utter social disaster. Second, regardless of whether you find it intuitive, this is simply what the best social science tells us about the effects of bans and prohibitions. In short, you’d find yourself in a very dubious epistemic position to deny it -- roughly the same position as you would be in if you rejected any other view that reflects a substantial scientific consensus.

To be clear: the argument here isn’t that prohibition wouldn’t affect the availability of guns; rather, it’s that prohibition wouldn’t affect their availability in socially desirable ways.

So what would work better than bans to reshape the market in guns to produce better social consequences? Yikes, I don’t know. I’m just a philosopher. But it would be surprising, I think, if the largest influence on the gun market, and so the largest influence on the mass production and relative availability of guns and the types of guns available, didn’t have something to do with the biggest spender on them. Compared to US federal and state government contracts, the private citizen market for weaponry amounts effectively to, if you’ll permit me to use a technical term, diddly squat. Imposing a ban on private ownership and exchange wouldn’t affect the supply side of the equation at all, and 1 suggests that’s what we should be concerned about.

The level of production and availability of weaponry in the US is driven by massive military, federal agency and state government spending. The impact of this spending on availability isn’t just that government surplus units can find their way into private hands. I’m sure that happens, but much more significant is the way government contracting magnitudes drive economies of scale for production, signal expansion in the industry, and incentivize both new firms and more and more units. Assault rifles are designed and produced with military and quasi-military applications in mind. This is the biggest market. The private consumer market is just spillover for producers. Second amendment enthusiasts and private protection stalwarts aren’t shaping supply. And waiting periods, registration and licensing requirements, magazine restrictions and excise taxes have little effect. Ditto buy-back programs or mandatory liability insurance. None of these measures are likely to make a significant difference on supply in the US when military spending is as high as it is.

Government expenditure on weaponry functions as a subsidy for guns. Subsidize something only if you want to get more of it. I recommend not doing this anymore (or drastically reducing this expenditure). Prohibition just makes things worse. Piecemeal regulations avoid the most significant problems associated with prohibition, but I doubt that any regulatory scheme would have an effect on reshaping the market in ways that would have a significant impact on weapons production (or tragic shootings) as long as total spending remains so high.

Kyle Swan

Philosophy Department

Sacramento State University

Kyle, thanks, there's a lot here I am inclined to agree with, but for reasons you don't give and which you might reject.

ReplyDeleteI think you will stipulate that lots of countries that are generally very nice places to live, by some measures nicer places to live than the U.S., permit very little in the way of private gun ownership and enjoy low levels of gun violence. Some of them may have illegal markets for the sort of weapons that are permitted here, but, if so, it doesn't appear to be the source of much gun violence, and the laws are not generally experienced as oppressive. It's plausible that the relation between prohibition and low gun violence is causal and it's just not clear that it's not worth it. In the U.S. there's lots of really dangerous stuff that private citizens are not allowed to own. I would not support legislation to legalize private ownership of military grade weapons or weapons-grade plutonium and I bet you wouldn't either. So we all accept this sort of thing in principle, and the question is just where.

But there is a big difference between countries in which citizens have never thought of private gun-ownership as a particularly good idea, much less a right, and the U.S., where we have enshrined it in the Constitution. Banning things we are used to having should not be expected to have the same effect as never having allowed them at all. It's reasonable to suppose that in the U.S. this would supercharge the black market, as you say.

My view is that we should someday repeal the 2nd amendment and let states decide how they want to handle private gun ownership. That's not going to happen anytime soon, but that's what we said about gay marriage and marijuana 20 years ago. Every succeeding generation is more liberal and its members more likely to live in urban centers where sympathy for gun ownership tends to run low. It's going to take a lot of time, and that is not a message anyone wants to give or hear whenever there is a school yard shooting.

Randy, right, I don't disagree with your third paragraph. But I meant to highlight that our relatively supercharged licit market is driven and shaped mainly the total size of that market, which is boosted so much more by state spending than people's interest in exercising their Constitutional right. The amount of that spending is another big difference between the US and other countries and, I think, a much bigger and under-appreciated part of the explanation for the problems we have here.

DeleteHey Kyle!

ReplyDeleteI am not really sure that I know the answer to this either, but I tend to lean towards solving for 1)fear and 2)ignorance.

It seems that some of the loudest 2nd amendment advocates are in fear of having to protect their own property (and lives) from the government itself. This might be alleviated if the spending by the military (and local law enforcement) were diminished as you suggest. This would also help to be alleviated if people didn't feel like the government was actually against them (taking/restricting rights, raising taxes, bailing out the banks, etc.)

To help curb the ignorance factor, well this is perhaps wrapped up in the fear argument or in the liberal movement of each successive generation as Randy mentions above. It is of course difficult as we are increasingly reverting back to tribal mentality...it's us against them. Blue collar vs white collar, gov't vs constituents, rich vs poor, black vs white, etc. Maybe even some neophobic tendencies thrown in. The only way we can curb that is by teaching kids rational thinking and some sort of social ethics (controversial, but I care not). Typical adults only seem to learn/change their point of view when they are faced with something "earth shattering" in their reality.

Sorry for the ramble, it's lunch time! :)

Kris, I'll see your ramble and raise you an unrelated observation. You talk about fear and ignorance. I'd like to talk about unfairness.

DeleteSpecifically, unfairness in the way crimes against buying, selling and possessing things are prosecuted, which is another dimension along which we can compare bans of drugs and guns.

In the case of a homicide, people call the cops to come deal with it and families of the victims pressure investigators and prosecutors to bring charges. But in the case of buying, selling or possessing drugs or guns, since there's usually no victim or complainant, the state has almost complete discretion about where they'll go looking for the illicit goods, who they'll stop and frisk, whose cars they'll search or call the dogs out for, who they will press charges against, whether (when) to stack charges or bring lesser charges, how they will sentence, etc.

The drug war is fought in an extremely unfair way, which has the effect of perpetuating racial injustices. There's no reason to think they'll operate differently when they start enforcing a ban on guns.

Hi Kyle, it's not clear to me that 2 always holds. Banning something that most people see as harmless, that most people have used, that many people own, that is relatively easy to make in a covert manner, that has a high value to weight/size ratio, that is easy to transport in bulk, and that is easy to use nearly anywhere without getting caught is very different to banning things with the opposite characteristics. Marijuana (especially for medical use) seems to have most or all of those characteristics, but military grade tanks for personal use (hunting? , home defense against someone else with a tank? ) seem to have few or none. A ban on tanks seems likely to be effective. Assault weapons are probably somewhere inbetween, so a ban may be effective. And, this ban can go hand in hand with decreasing military spending (or spending military funds on armour or rehab etc for vets instead of on weapons).

ReplyDeleteThanks, Dan. I agree that all those factors affect the strength of the case for 2. But three related things in response: first, another factor, one I suggested was way under-appreciated, is the total size of the market, like whether or not it's getting a state subsidy to the tune of $600 million. Second, when you say that a ban may be effective, effective for what? I said the evidence is that bans tend to redirect, rather than eliminate, markets in the banned things. So I don't think a ban would have no effect. I just don't think it will be a positive one. For example, if you ban assault rifles, you might eliminate private ownership of the kind of assault rifles we see people with now (but, geez, they're still going to be made -- the military probably won't stop using them). But, even if you do, those resources will be redirected somewhere. Possibly, you'll see a lot more homemade kits or "printed" versions. This suggests the third thing. Assault rifles are relatively simple machines of metal and plastic, easy to make, assemble, store, transport, repair, and operate. In short, quite a bit more like drug trade marijuana than you seem to be allowing.

DeleteKyle, nice post. These sorts of consequentialist arguments usually don’t appeal to me, but, even from a consequentialist perspective, I think there are a couple additional points or factors worth considering.

ReplyDeleteFirst, your second point is that bans are particularly bad ways of dealing with harmful products. You argued that a ban would redirect, rather than eliminate, the market on assault rifles—a continued proliferation of an unregulated black market on assault rifles. At the end of your post, you mentioned that prohibition would make things worse. I think there’s an important difference between being ineffective and making the situation worse, particularly when prohibition may involve other social benefits, maybe less tangible benefits (see below). Between prohibition (P) and no-prohibition (NP), if neither is more effective than the other at curbing certain bad social consequences, then there is no reason to prefer P over NP and there is no reason to prefer NP over P. Do you think P is worse (are there facts to support this)?

Second, between P and NP, I’m skeptical that neither is more effective than the other at curbing gun violence.

I think there are other social benefits of P that ultimately may have an effect on gun violence. I would call these expressive benefits.

David Luban, in supporting international criminal trials (which are still largely ineffective in deterring human rights violations and prosecuting those who commit mass atrocities), argues that their main benefit and justification is their role in “norm projection.” International criminal trials, he says, are expressive acts that mass atrocities are heinous crimes rather than politics by other means. They allow the international community to express moral truth against those who carry out such crimes.

James Nickel similarly argues that human rights documents, though maybe ineffective in securing human rights for the oppressed, also serve the purpose of establishing norms, providing grounds for disapproval and criticism, and guiding domestic reform.

Here, P may send the message that gun violence and assault rifles, in the hands of civilians, will not be tolerated. When Emma Gonzales calls legislatures to do something to end mass school shootings, this is an expressive act. If legislatures respond to enact legislation banning automatic and semiautomatic assault weapons, this too would be an expressive act--one that serves the purpose of norm projection. An act that does something rather than nothing and offers at least the hope of social change.

Thanks, Chong. I wasn't saying two alternative things there. Rather, the empirical evidence is that the ways prohibitions and bans effect the market in illicit goods (the ways the laws redirect and reshape the market) tend to make things worse.

DeleteIf legislatures respond to calls to do something by enacting legislation banning these weapons, they won't merely be engaged in an expressive act. They will also be subjecting people to very real harms (including, for example, the harms associated with the unfairness I talked about when I replied to Kris above).

Kyle, thanks for clarifying.

DeleteI guess I’m skeptical--not of the harms of which you speak, but that they outweigh other social harms (or the deprivation of certain social benefits). Part of the problem lies in assigning weight to these harms and benefits, especially but not only the intangible ones.

As others seem to be suggesting, there may be a morally significant difference between goods that are not in themselves bad or dangerous, but they may be used or abused in ways that are dangerous, and goods that are inherently dangerous to human life.

“Bans and prohibitions are particularly bad ways of dealing with problems or harms stemming from the availability of some object, substance or service.”

What about child pornography? Prohibition wouldn’t affect the availability of child porn in socially desirable ways?

It seems to me that certain goods such as any form of child pornography is so inherently dangerous that, even if prohibition results in an illicit market for the good, prohibition is justified by the greater social harms in allowing it or the greater social benefits in prohibiting it.

Bans and prohibitions tend to produce a lot of social harms, but some of the ones I worry about (like in my reply to Kris above) have to do with buying, selling or possessing things where there aren't typically victims or complainants. I think that's different than child porn (or other things in which there is illicit trade, like slaves, murder for hire, stolen goods, counterfeit money, etc.).

DeleteSecond, the harms that have more to with the effect of a ban or prohibition on the shape of the market depends on empirical factors like the size of the resulting shifts of the supply and demand curves and how sensitive quantities demanded and supplied are to changes in price. But 1) I don't know of any credible study that shows that prohibition is an effective, long-term way to reduce quantity supplied; and 2) this would be especially unlikely in the case of guns given that massive amounts of money are routinely budgeted (not just spent there, but budgeted!) to the industry.

Kyle,

ReplyDeleteYou never disappoint, do you?

Two responses to your post:

1. Shouldn’t a proposal to ban/prohibit, or even regulate, some good consider the question of its right use? Specifically, it should consider how wide gulf there is between right use and misuse.

The evil of Prohibition hinged on its obliteration of this distinction. The 18th Amendment went into effect in 1920, but it wasn’t until 1922 that Internal Revenue got around to providing permits for altar wine. So for two years the sacramental life of the Catholic Church, ‘right use’ surely, constituted a violation of federal law. But there was always a great gulf between the right use of alcoholic beverages and misuse. For many cultures its consumption is a central feature of the good life.

Contrast alcoholic beverages with opioids. The latter are, of course, a great good: it’s difficult to imagine the practice of medicine without them. However, given their addictive powers, the gulf between a right non-medical use and misuse is perilously narrow. We should be open to the conclusion that the gulf does not exist. If so, the non-medical use of opioids may reasonably be regulated or banned.

Sure, that's relevant. But it's relevance doesn't entitle you to your last sentence because there are so many other things that are relevant -- like the harmful social effects of prohibitions and bans.

DeleteHere's a question...

ReplyDeleteAre firearms like opioids or like alcoholic beverages?

The answer is evident. The scope for the right use of firearms is very great, the gulf separating such use from misuse very wide. Leaving aside hunting, and the innocent heckafun of punching holes in paper targets on the range, the central right use of firearms is in defense of self, loved ones, and fellow citizens. A liberal state is a mutual pact among its citizens in defense of their lives and rights. Liberal theory is the acknowledgement of the human potential for violence, and the wrongness of a pacifist refusal to reciprocate your neighbors’ readiness to defend you. Another central right use is in deterring rights violations by the state itself. The fact that there is a gun for every citizen in the U.S. is a seldom-recognized guarantor of mild government. (My personal speculation is that Americans would make fearsome insurgents, and good for us.) Great Britain has long banned guns. The Lord Mayor of London now favors the banning of pointed kitchen knives.

When sporks are outlawed only outlaws will have sporks.

Given the widespread distribution of firearms in the U.S. it is more surprising that the level of violence is as low as it is.

One argument for banning the non-medical use of opioids is the impossibility of regulation, since it is unknowable in advance who would succumb to addiction and who wouldn’t. But a reasonable regulation regarding who may possess firearms is readily enforceable.

A policy with a better chance of reducing gun violence would be a more interventionist approach to mental health. Such an approach would also mitigate our current callous approach to fellow citizens, which confuses individual freedom with inhumane indifference. Permitting homelessness is not a ‘right use’ of liberty.

2. Whether military procurement drives the gun industry in some significant way is an empirical question.

ReplyDeleteHere are some considerations pointing to an answer.

The two gun types creating the real issue are ‘assault rifles’ and magazine-fed semiautomatic handguns. The Department of Defense buys its standard rifle from Colt. No civilian can buy that version, since it incorporates a three-round burst setting. But the civilian semi-automatic-only Colt is really expensive, so they constitute a very small part of the market. A revealing picture of that market is the Bud’s Gun Shop website (budsgunshop.com) . Go to the ‘AR Rifles For Sale’ page for an idea of how many different manufacturers produce part-for-part the same gun: Bushmaster, Windham Weaponry, DPMS, Del-Ton, Smith & Wesson, SIG Sauer, Rock River Armory – the list goes on for pages. Then do a search for ‘AK 47,’ where you will find a list for a civvie version of the commie rifle that’s almost as long. Then type in ‘FN FAL’ for the standard rifle of most European NATO countries.

Regarding handguns, the situation is even starker. Until last year the DOD standard issue was from Beretta, an Italian firm. It’s due to be replaced by a SIG Sauer product made in Germany and Switzerland. An even more limited but still revealing picture of the civilian handgun market is the California DOJ Bureau of Firearms ‘Roster of Handguns Certified for Sale.’ (oag.ca.gov). It takes minutes just to scroll through the list, from Accu-Tek to Wilson Combat. The number of different magazine-fed semiautomatic handguns listed is, simply, dizzying. It’s also incomplete since the roster includes only those manufacturers willing to put up with California’s punitive certification process (Makarov, Girsan, and Tisas simply don’t bother).

All these weapons are ‘legacy’ technology. Eugene Stoner’s design for the AR is over 60 years old. Kalashnikov’s AK 47 goes back to World War II. The most famous magazine-fed semiautomatic pistol is fondly known as the ‘1911’.

My highly tentative conclusion, then, is that military procurement’s contribution to the gun industry is both miniscule in scope and in the distant past.

The effect of the government's huge expenditures on weaponry isn't limited in the way I think you're suggesting to the specific firms it contracts with. That's where the money is injected into the market, but the magnitude of the injection will still drive economies of scale for production throughout the entire industry, sending signals to expand, and incentivizing both new firms and more and more units. A capital injection, or the equivalent of one, into one firm will typically have an expansionary effect for the entire industry. The downstream effects of the financial bailout for that industry went far beyond the individual firms that received the funds.

DeleteHi Kyle,

DeleteI’m not limiting the effect of government expenditures just to those firms with DOD procurement contracts.

You are entirely correct that money paid to Colt goes to Colt’s suppliers of, say, trigger assemblies and milspec lower receiver aluminum blanks. And those companies sell their stuff to the other gun manufacturers too.

My point is that, however huge government’s expenditures on weaponry, the civilian market in the U.S. is gynormously yuuuuuger. That market was there all along and will continue to be there whatever military and government does.

Ah, got it. Thanks. I'll look into it more.

DeleteIt looks like total revenues of the firearm industry is 1/10 of the US military procurement budget alone.

DeleteThe relevant comparison would be the military's expenditure on small arms.

DeleteUS military spending makes up 34% of total industry revenues. In 2012 it was 25% (and state law enforcement was 15%). This article was interesting: http://theconversation.com/how-the-us-government-created-and-coddled-the-gun-industry-85167

DeleteThanks for that info, Kyle. I would have thought that the civilian market was several times larger than the military/government market, rather than roughly the same size. I would point out, though, that this is more than 'diddly squat.'

DeleteI'm still not sure that your proposal to limit military/government procurement would produce as much of an effect as you would have it produce.

There will still be a vigorous civilian market. DeLay's article has no explanation how the gun industry foisted their product off on otherwise unwilling customers on such a scale. The best explanation is that the customers wanted them.

If our governments at all levels lower their level of support, there will still be fine, inexpensive Czech and Brazilian and magazine-fed pistols and Bulgarian AK's available from Bud's.

And you're against banning them.

You would point that out, wouldn't you?

DeleteBut three things: first, I noted that 'diddly squat' was a technical term. I now hereby clarify that it refers to an amount roughly between 50-60% of some total.

Second, slightly more seriously, I did preface the positive part of my post by admitting that I'm just a philosopher and we get to make stuff up. I was just taking a stab at an explanation.

But, third, I still think you're dismissing it too quickly. Because, take an industry with about $7 or 8 billion (about the size of the *civilian* market for guns). Don't you think an injection of $6 or 7 more would have a significant effect on the availability of the product? But that's just a static picture. In the case of guns, the military and US and state agencies have been involved in this market to a very significant degree from the beginning and tilting it towards military and quasi-military applications. So it's not just that they have effected the size of the market and the availability of the product, but also what the product would be like. This is also part of what I referred to as the shape of the market.

So, even with a better picture of the empirical data, the explanation still seems plausible to me.

Thanks for the reply, Kyle.

DeleteSeveral points.

The two issues between us seem to be what makes for 'availability' and 'what the product is like.'

You conceded the tentative nature of your proposal regarding availability, just as I conceded the tentative nature of my argument that it wouldn't work. It still seems plausible to me.

(So why should any sensible person be reading this thread?

As far as your original fine blogpost goes, we're way down in the weeds here.)

Regarding the nature of the product, 'military and quasi-military applications' seems to mean 'suitable for defense of our lives and rights.' If that is a right use of firearms, this kind of gun is just what we would expect the citizenry of a liberal state to be a market for.

Regarding 'market redirection,' one of the unintended effects of the altar wine permits under Prohibition was a corrupting effect on some Catholic clergy.

ReplyDeleteThey became bootleggers.

Corrupting effect? More like fulfilling their duty to magnify their callings.

DeleteKyle,

ReplyDeleteI suspect that as a group ordinary American citizens vastly outgun government at every level.

Kyle, thanks for this. I'm inclined to agree with you here, but I wonder how you'd respond to a question and a proposal.

ReplyDeleteQuestion: why do folks persist in thinking, of drugs or guns or something else, that (to use your language) "prohibition WOULD affect their availability in socially desirable ways"? Is it because prohibition sometimes (often?) does so work on much smaller scales, like parents keeping certain things away from their kids in the confines of their own home? Not saying this always works (especially once the kids outnumber the parents!), but is the "nanny state" just really bad at what it does when it "nannies" because there are too many people to manage? (You could reply that even parental prohibition is just too darn inefficient because it "redirects..." and so let's just try to adjust the supply and demand curves in some other way...)

I wil get to the proposal later. Right now I gotta chase a kid down who managed to get some contraband...

Hayek argued that there were two different kinds of order: taxis (exogenous, planned or constructed) and cosmos (endogenous, unplanned or spontaneous). He uses the distinction for a couple different purposes that are relevant here. First, especially in large groups, the latter can easily subvert the top-down designs of the former. This is easily seen in markets for banned substances. This doesn't mean that top-down commands have no effect, just not all and only the effects that were intended. But second, a lot of our moral intuitions are leftover from earlier phases of human development occurring in small, face-to-face, top-down organized groups. It's hard to resist attempts to apply the organizational thinking of premodern clans to modern, complex, spontaneous orders. (But he also said that it's just as much a mistake to apply the ethos of the small group or family to the broader society as it is to apply the ethos of the extended order to the family!)

Delete